A Narrative from a Position of Inquiry, Not Authority

Entertainment in Public: Reconstructing the Microhistories of Objects and Bodies at the Intersection of History, Philosophy, Art, and Technology

By Hossein Ganji

20 February 2025 Critique

Shargh daily

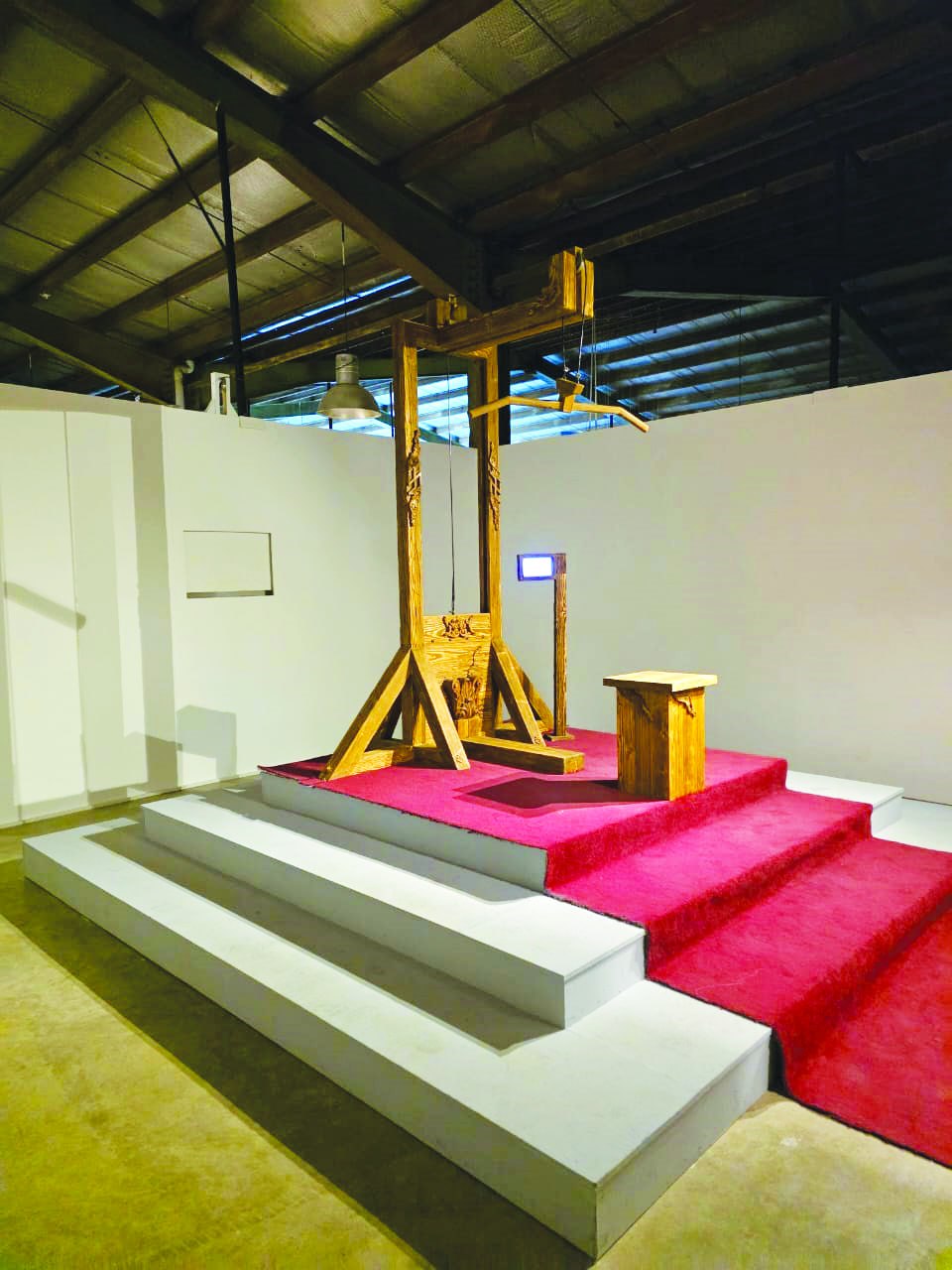

The exhibition Entertainment in Public, held at the Daheem Innovation and Art Factory and curated by Taha Zaker with curatorial direction by Hoda Sargardan, is an interdisciplinary and experimental project that endeavors to narrate history not through written language or official memory, but through objects, technology, and the embodied experience of the audience. Focusing on the events following the French Revolution and the guillotine—an apparatus that played a significant role in the domains of power, justice, and violence for over two centuries—the exhibition seeks to extricate the object from its neutral, museological state and transform it into a focal point for historical reconsideration by employing diverse platforms and contemporary technologies.

This project is not merely an exhibition; it functions as an “anti-museum” a space where objects are not displayed behind glass cases in the customary silence and distance of traditional museums but are arranged in a manner that invites the audience into a bodily, experiential, and even psychological engagement with history. Simultaneously, it stands as a research-based exhibition and museum where the works do not merely present themselves but carry historical, philosophical, and humanistic narratives. In Entertainment in Public, history is recounted through objects, which serve not merely as documents of the past but as mediators for a living, personal, and thought-provoking encounter with history.

A Personal Narrative of an Object’s History

As Taha Zaker notes in his statement, the initial idea for this project originated from watching a video on Instagram; a television speech that presented a fallible yet provocative narrative suggesting that Western freedom has been accompanied by blood, death, and violence, and that those who claim moral superiority today have forgotten their own past. Zaker writes:

“Objects have always captured my attention. This project is my narrative of an object’s history. I believe objects convey the most honest account of history.”

Zaker, through a narrative-driven arrangement, depict the formation of civilization emerging from violence, freedom arising from bloodshed, and humanity evolving from cruelty, using historical passages from the events following the French Revolution and the process of issuing and executing death sentences from the guillotine to the technological apparatus of electricity.

In this perspective, history is no longer a collection of data and events to be gathered and classified but a platform for individual, critical, and sensory storytelling of the past, as Walter Benjamin articulates in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”:

“There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

This exhibition perhaps reinterprets Benjamin’s viewpoint, suggesting that objects are more truthful narrators, and that execution devices themselves testify to humanity’s passage through immense cruelty and injustice a path that transforms yesterday’s freedom-seeking, dialogue supporting human into an inhumane, monologue driven entity.

The guillotine, as the central object of this project, has been both an instrument of justice and a symbol of oppressive power. It has been invoked In the name of revolution and in the name of terror. This multiplicity renders it a complex, contemporary object, open to reinterpretation in today’s social context.

Technology as a Narrative Tool

In this project, technology is not employed for decoration or audience attraction but to generate a novel experience of “contact with history.” Visitors to the exhibition are not merely observers of video art, computer games, costume design, and documentaries; they become participants in an interactive experience. Here, technology serves as a medium for establishing direct contact with historical objects and, ultimately, for a thought provoking engagement with history.

This approach echoes the perspective of thinkers like Marshall McLuhan, who stated:

“The medium is the message.”

In this context, the medium of storytelling is the object itself, and through technology, the object becomes alive, responsive, and narrative. The audience’s encounter with the guillotine, through video representations, sound, light, and space, becomes a fully embodied and contemplative experience.

Microhistories Versus Official Narratives

The exhibition’s focus on the microhistory of the guillotine entails concentrating on narratives that have remained silent or marginal in official history. Contrary to grand narratives where history is recounted in the language of conquerors and rulers, this project reinterprets the guillotine as an apparatus (in Foucault’s terms) that not only narrates death but also reveals the dynamics of power and the body.

Similar to Montesquieu’s Persian Letters, where the author critiques French society through the device of a foreign observer, this project attempts to critique society through the “language of objects” rather than the human subject. Montesquieu utilized the voices of Uzbek and Rica to reflect his society through the mirror of another; in Entertainment in Public, objects serve as that mirror.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, regarding Persian Letters, wrote:

“In this book, by encouraging the noblest feelings, Montesquieu directs the French nation towards its most pressing duties.”

This same pattern is evident in this project. Narration through the voices of objects confronts us with our forgotten responsibilities towards history, justice, and the body.

Body, Space, Violence

The exhibition’s arrangement in an industrial warehouse, with limited lighting, silence, and meaningful distances between works, becomes part of the audience’s psychological and physical experience. The visitor’s body in this space engages with questions concerning “the history of the body,” “visual violence,” and “the role of the spectator,” ultimately confronting the reproduction of violence. This embodied perspective distinguishes it from traditional exhibitions and museums, transforming it into a pedagogical experience.

According to Georges Bataille’s theory, violence and death are not concealable but foundational to aesthetic experience. In Literature and Evil, he suggests that art must approach the most unacceptable layers of human experience. In this exhibition, the aesthetics of execution objects reflect the dynamics of power, the body, and guilt.

Philosophy, Humanity, and Humanism

Inspired by the thoughts of Foucault and Latour, the exhibition demonstrates that objects like the guillotine are not merely tools but apparatuses that intertwine knowledge, power, and bodies. This perspective extends agency beyond the human subject to a network of humans, objects, and institutions. The representation of the body in the exhibition’s arrangements recalls Foucault’s concept of “punishment in public view.” The deprivation of life is no longer a hidden event behind closed doors; the spectacle of death becomes entertainment. This phenomenon persists in modern societies through the media portrayal of violence and punishment.

One of the most somber lessons from the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror is precisely this: many of the initial revolutionaries, such as Danton and Robespierre, became victims of the very system they helped create. As Hannah Arendt writes in The Origins of Totalitarianism, revolutions that rely solely on revolutionary fervor and mass emotions, without the restraint of civil institutions and law, reproduce violence.

Taha Zaker’s project, by emphasizing “microhistories,” seeks to portray the overlooked, the eliminated, and the bodies that have no place in official history. The narrative of the guillotine here is not merely about an execution device but symbolizes the ideological neglect of the “other.”

Freedom, without continuous self-critique and without vigilance over the tools employed in its pursuit, can transform into its own antithesis. If the French Revolution initiated modern human rights discourses, the guillotine serves as a reminder that even in the name of freedom, one can become an instrument of another’s oppression. Entertainment in Public is not merely a museum or an avant-garde installation; it is a mirror. A mirror that, if we look into it carefully, may reveal our own faces as part of the spectators of “public entertainment.”

Our Relationship with the Project

The exhibition is held at a particular juncture—a time when violence, both symbolic and real, continues to pervade various domains, and objects of power (from gallows to legal terminology) are still publicly displayed. Although this project concerns post-revolutionary France, it undoubtedly serves as a mirror for reflecting on our own condition; watching the “public entertainment” of others sometimes conceals a narrative about ourselves. We, who attend executions and perceive them as entertainment, must remember that such events were intended as lessons, not reproductions of what is undesirable.

By referencing the history of public executions—not only in France but as a global practice—and recalling the fate of those who remain in history not by name but through their bodies, the exhibition attempts to summon forgotten violence through the aesthetics of objects.

Narration, Resistance, Reconsideration

Entertainment in Public can be seen as an effort to reconsider history—not through grand narratives but through small objects, individual experiences, and embodied encounters—and, on the other hand, as an invitation to rethink the philosophical concepts of humanity and freedom, especially when humans embrace power and cease to be advocates of freedom, becoming its agents instead. This project transforms the observation of history into a lived, critical, and multimedia experience—not from a position of knowledge, but from one of inquiry.

If Walter Benjamin taught us that history must be reread from the perspective of the defeated, this project reconstructs their image through the very tools that destroyed them. The guillotine, once constructed for justice, in this narrative becomes an apparatus for contemplating the failure of justice—a place where, in the name of freedom, injustice reigned, and violence manifested in various forms, perhaps even appearing modern and legal.

Ultimately, this project is not merely about the history of an object but about our relationship with history, power, the body, and technology. In an era where history is rapidly consumed in media and politics, Entertainment in Public is an invitation to pause, to observe objects, and to listen to what is usually left unsaid.

The exhibition Entertainment in Public can be considered an attempt to bridge art, history, philosophy, and technology—a project that, through the language of objects, summons the voices of history’s forgotten. This project is not only about the past but poses questions about the present: our relationship with violence, with spectacle, with the body, and with truth.

- Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, 1940.

- Marshall McLuhan, ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’, 1964.

- Michel Foucault, ‘Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison’, 1975.

- Charles de Montesquieu, ‘Lettres persanes’, 1721.

- Georges Bataille, ‘Literature and Evil’, 1957.

- Hannah Arendt, ‘The Origins of Totalitarianism’, 1951.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘Phenomenology of Perception’, 1945.

- Jacques Rancière, ‘The Emancipated Spectator’, 2008.

- Carlo Ginzburg, ‘The Cheese and the Worms’, 1976.

- Susan Sontag, ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’, 2003.

- Bruno Latour, ‘Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory’, 2005.

This critical essay was originally published in Shargh Daily on May 6, 2025, as part of its art and culture section.

This critical essay was originally published in Shargh Daily on May 6, 2025, as part of its art and culture section.

آخرین اخبار Art را از طریق این لینک پیگیری کنید.